Why Is Friday the 13th Unlucky? The Real History Behind the Superstition

It's that time again for everyone's favorite unlucky holiday, Friday the 13th! And funny enough, the slasher series from which Kevin Bacon's career was launched and hockey-masked mass killer Jason Vorhees (and his murderous mother) emerged started only from a title. Producer Sean S. Cunningham was inspired by the success of John Carpenter's Halloween and wanted to make his own horror movie in that vein. So taking the ingredients of that seminal horror movie, he grabbed a spooky holiday name and found a mask for the killer to wear, and he even ran in ad in International Variety magazine giving a timeframe for the debut of the film before a script was finished. The title came before the movie and it worked! Friday the 13th spawned ten sequels and a remake in the thirty years since it debuted.

But why do we think of that day as unlucky?

It's Actually Two Separate Superstitions Mashed Together

Here's the thing most people don't realize: "Friday the 13th" as a single unlucky concept is surprisingly modern. The number 13 has been considered unlucky for centuries, and Friday has independently been considered an unlucky day for centuries, but as folklorist Steve Roud documents in

The Penguin Guide to the Superstitions of Britain and Ireland, the combination of the two into one superstition is a Victorian-era invention, with the first concrete English-language reference to the specific bad luck of Friday the 13th appearing around 1913.

Why Is the Number 13 Unlucky?

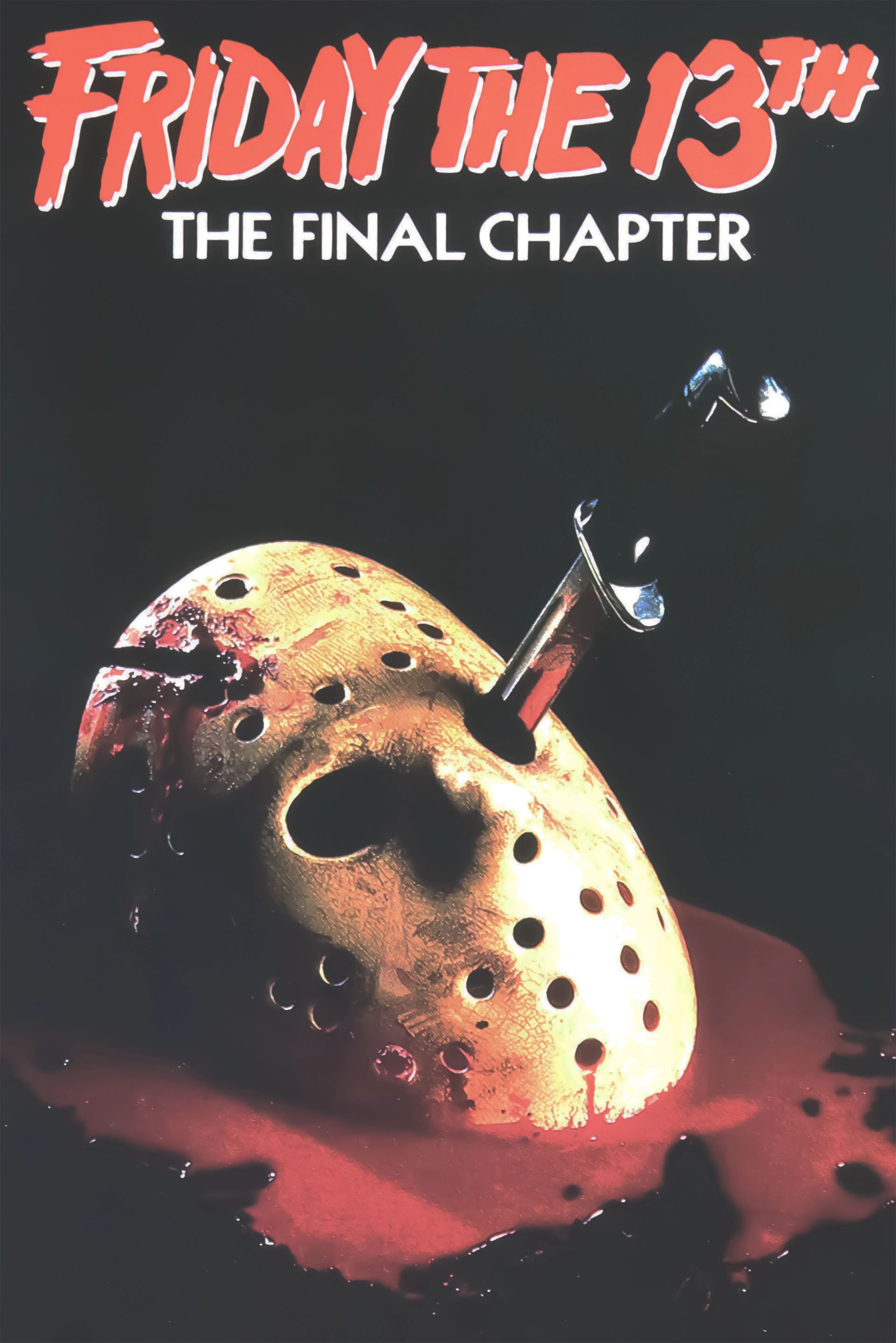

The Last Supper

The most commonly cited origin ties back to Christianity. There were 13 people seated at the Last Supper, Jesus and his twelve apostles, and the 13th to sit down is traditionally said to have been Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus. This gave rise to a longstanding superstition that having 13 guests at a table was courting death, though this specific association appears to have solidified in the medieval period rather than in early Christianity.

Norse Mythology

An older parallel comes from Norse mythology. In the story, 12 gods were feasting in the great hall of Valhalla when Loki, the trickster god, showed up uninvited as the 13th guest. Loki then manipulated the blind god Höd into killing his brother Balder, the beloved god of light, with a mistletoe-tipped arrow. The death of Balder plunged the world into mourning.

12 as the "Complete" Number

There's also a simpler mathematical/cultural explanation: Western civilization is steeped in the number 12 as a symbol of completeness. Twelve months, twelve zodiac signs, twelve hours on a clock, twelve tribes of Israel, twelve labors of Hercules, twelve gods of Olympus. The number 13 breaks that neat pattern, it's the interloper, the one too many.

The clinical term for fear of the number 13 is triskaidekaphobia — coined in 1908 in Religion and Medicine: The Moral Control of Nervous Disorders by Elwood Worcester, Samuel McComb, and Isador H. Coriat.

Why Is Friday Unlucky?

Friday's reputation as an unlucky day also has deep roots in Christian tradition. According to various Biblical traditions:

- Jesus was crucified on a Friday (hence "Good Friday," though the day itself carried an ominous weight).

- Friday is said to be the day Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit from the Tree of Knowledge.

- It's also been associated with the day Cain murdered his brother Abel, and the day the Great Flood began.

The literary record backs this up: Geoffrey Chaucer references Friday as an unlucky day in

The Canterbury Tales (late 14th century), warning readers not to begin a journey or start a project on a Friday. However, broader references to Friday as generally ill-fated in English sources don't become common until around the mid-17th century.

So When Did "Friday the 13th" Become a Thing?

The Earliest Known Written Reference (1834)

The earliest known written reference linking Friday and the 13th comes from 19th-century France. An 1834 article in the French literary magazine Revue de Paris, written by Italian author Marquis de Salvo, references a Sicilian count who killed his daughter on Friday the 13th.

It Hits the English-Speaking World (Late 1800s–Early 1900s)

In the late 1880s and early 1890s, references to a belief in Friday the 13th begin showing up regularly in American newspapers. But the superstition truly exploded into popular consciousness with Thomas W. Lawson's 1907 novel

Friday, the Thirteenth, in which an unscrupulous Wall Street broker deliberately exploits the superstition to crash the stock market. The book was a hit — it sold over 60,000 copies in its first month. After publication, stockbrokers allegedly refused to trade on any Friday the 13th.

What About the Knights Templar?

This is the one you've probably heard: On Friday, October 13, 1307, King Philip IV of France ordered the mass arrest of the Knights Templar. Hundreds of members were seized, including Grand Master Jacques de Molay. The charges of heresy, idolatry, and sodomt were largely fabricated; Philip was deeply in debt to the Templars and wanted their wealth. Many Templars were tortured into false confessions and eventually executed. De Molay himself was burned at the stake in Paris in 1314.

It's a real historical event, and it really did happen on a Friday the 13th. But historians are skeptical that it's actually the origin of the superstition. The connection between the Templar arrests and the Friday the 13th superstition was popularized much later, most notably by Dan Brown's 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code. Historian Helen Nicholson of Cardiff University has noted that many of the rationalizations linking the Templars to the superstition are relatively recent inventions.

Author Nathaniel Lachenmeyer, who has researched the superstition extensively, argues that before the 20th century, "13" and "Friday" were separately unlucky, but "Friday the 13th" wasn't really a unified concept, making the Templar connection a case of retrofitting history to fit a modern belief.

The Thirteen Club: A Victorian Attempt to Fight Back

Not everyone has taken this lying down. At 8:13 p.m. on Friday, January 13, 1882, Captain William Fowler, a Civil War veteran whose life was so entwined with the number 13 it bordered on absurd (he attended Public School No. 13, fought in 13 battles, and bought his bar on September 13), gathered 12 brave souls in room 13 of his Knickerbocker Cottage on Sixth Avenue and founded The Thirteen Club. To reach their meal, guests walked under a ladder and past a banner reading "Morituri te Salutamus" ("Those of us who are about to die salute you"). Salt cellars were deliberately overturned. The first of 13 courses was lobster salad molded into coffin shapes.

The club grew rapidly, from 13 members to over 1,300 by 1889. Four U.S. presidents (Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, and Theodore Roosevelt) joined its ranks.

It's Not Universal

Friday the 13th isn't a global superstition. It's largely a Western (especially Anglo-American) phenomenon.

- In Spain and Latin America, the unlucky day is Tuesday the 13th (martes trece). There's even a saying: "En martes, ni te cases ni te embarques" — "On Tuesday, don't get married or set sail."

- In Italy, it's Friday the 17th that's considered bad luck.

- In Greece, Tuesday the 13th is the feared date.

The Modern Impact

The fear of Friday the 13th has its own clinical name: paraskevidekatriaphobia (from the Greek paraskevi for Friday, dekatreís for thirteen, and phóbos for fear), coined by psychotherapist Donald Dossey.

The superstition has real economic consequences. It has been estimated that $800–$900 million is lost in American business on each Friday the 13th, as people avoid travel, delay purchases, and postpone major decisions.

And yet, a 2008 study by the Dutch Centre for Insurance Statistics found that fewer traffic accidents, fires, and thefts were actually reported on Friday the 13th compared to other Fridays, likely because superstitious people simply stayed home.

While Jason Vorhees might get all the credit, it's the obscure Friday The 13th: The Series that I enjoy the most when I think about the holiday. It was a low-budget horror show that was syndicated in the late 1980s and it was just gruesome and scary enough to leave a lasting impression on me. It was all about a shopkeeper who made a deal with the Devil (the late great RG Armstrong, who played the general who gave Arnold and Carl Weathers their marching orders in Predator, as well as taking on the Warlock in that film's misbegotten sequel) and he sold cursed antiques in his store. After he dies and his soul goes to Hell, his younger relatives inherit the store and it's up to them to get the cursed items back.

Every episode of Friday the 13th: The Series was basically the same, where someone comes into contact with one of the items and it promises them fame, money, sex, adoration, etc... but people have to be killed to feed it. If they stop killing, then they stop getting what they want, and well, once you get a taste, you never want to give it up. Anyway, this show is why I'm always wary of seeing things that are too good to be true, because there is no magic pill and you never get something for nothing.

Anyway, my Friday the 13ths haven't been particularly unlucky, but I have had several strange occurrences on the 12th of the month in the past. Coincidence?! Who knows, maybe 12 isn't a "complete" number for me. But whatever your luck is right now, it's always in our power to turn it around. So, here's a little salt to throw over your shoulder... just in case.

Stock photos provided by depositphotos.com