The Wendigo Legend: Real Stories, Native Folklore, and Hauntings

What Is a Wendigo?

The Wendigo is a terrifying creature from American Indian folklore, especially among the Algonquin-speaking tribes of the Great Lakes region, Canada, and Northeastern U.S. It represents the horror of insatiable greed, selfishness, and cannibalism, born in times of winter famine and spiritual imbalance.

Long before it became a staple of horror movies and video games, the Wendigo haunted the dreams of Indian communities across the north, a monstrous warning about what happens when we lose our humanity.

Wendigo Folklore Origins: A Spirit of Winter and Hunger

The earliest written account of the Wendigo appeared in 1661 in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, describing Cree tribesmen who turned cannibal during a brutal winter. Jesuits reported:

“Those poor men were seized with an ailment unknown to us… [which] makes them so ravenous for human flesh… they were slain in order to stay the course of their madness.”

To Ojibwe, Cree, and Wabanaki peoples, the Wendigo was more than a monster—it was the embodiment of gluttony, isolation, and spiritual corruption.

What Does a Wendigo Look Like?

Forget Hollywood’s horned cryptids. In authentic Native American Wendigo legends, the creature is described as:

- Emaciated and towering, sometimes 15 feet tall

- Gaunt, pale skin stretched tight over bones

- Bloody, chewed lips and gnawed fingers

- A heart encased in ice

- So ravenous it eats its own body

Its terrifying transformation symbolizes the way greed can consume a person—literally and spiritually.

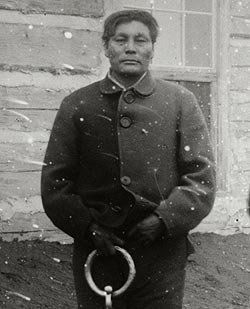

Real Wendigo Story: The Case of Swift Runner

One of the most infamous real-life Wendigo cases is that of Swift Runner. Swift Runner (also spelled Swift-Runner or S’wift Runner) was a Cree trapper, hunter, and former member of the North West Mounted Police. He lived in what is now Alberta, Canada, north of Edmonton. He was known in his community, a respected figure—until the winter of 1878–79.

That year, Swift Runner took his wife, six children, his mother, and his brother into the remote forest to hunt and trap for the season, as was customary for Cree families during the harsh Canadian winters.

In the spring, only Swift Runner returned.

He told authorities that his entire family had died of starvation during the severe winter, and he alone had survived.

But something wasn’t right.

Swift Runner didn’t look like a man who had endured starvation. In fact, he appeared healthy and well-fed. This aroused suspicion.

When investigators traveled to Swift Runner’s winter camp, what they found confirmed their worst fears:

- Human bones scattered around the site

- Evidence that bodies had been butchered and cooked

- A pot full of human fat

- Bones broken open, presumably to extract the marrow

Swift Runner confessed to the murder and cannibalism of his entire family, including his youngest son, whom he killed after spring arrived, when game and supplies were once again accessible.

This crucial detail ruled out starvation as the motive. Swift Runner insisted he had been possessed by the spirit of a Wendigo—the monstrous, cannibal spirit from Cree and Algonquin folklore.

Swift Runner was tried and convicted in Fort Saskatchewan in 1879. He confessed openly, not denying any of the charges. Reports say he showed remorse, and even joked with the priest before his execution. Still, his crime shook the region.

He was hanged that same year, the first legal execution in Alberta.

Wendigo Psychosis

Swift Runner’s case became a foundational example in the study of “Wendigo psychosis”, a controversial culture-bound syndrome described in early psychiatric literature.

Symptoms of Wendigo psychosis include:

- Depression and withdrawal

- Insomnia and paranoia

- A growing belief that one must consume human flesh

- Cannibalistic urges, even when other food is available

Modern psychiatry no longer recognizes it as a formal disorder, but anthropologists and psychologists still debate whether Swift Runner was:

- Suffering from a mental illness interpreted through a cultural lens,

- Truly experiencing spiritual possession,

- Or using the Wendigo as a socially comprehensible excuse for acts he was already inclined to commit.

In some Wendigo lore, once someone tastes human flesh, their heart becomes encased in ice, and there’s no way back. Only death can cure the Wendigo.

Swift Runner’s story mirrors that mythology exactly: he crossed the line, and the transformation from man to monster was complete.

The Wendigo on Madeline Island near Bayfield, Wisconsin

Madeline Island, the largest of the Apostle Islands in Lake Superior, is a sacred site for the Ojibwe and steeped in supernatural lore. While modern authors have sensationalized it with tales of cannibalism, traditional stories speak more to spiritual transformation and protection.

In one traditional Ojibwe Wendigo story collected near Madeline Island, a little girl defeats a massive ice giant by transforming into a giant herself and using magical copper staffs to reveal the emaciated human inside.

Even today, island residents speak of ghost sightings, haunted museums, and strange figures spotted after the first snowfall—echoes of Wendigo legends that never fully disappeared.

Wabanaki Wendigo Legends and Bar Harbor’s Chenoo

Near Bar Harbor, Maine, the Wabanaki tell stories of the Chenoo, a localized version of the Wendigo. But here, the monster can be redeemed. One tale tells of a woman who shows compassion to a cannibalistic ice giant, slowly nursing it back to humanity with kindness, warmth, and hot bear fat soup.

This version of the legend doesn’t end in death, but in forgiveness and healing which is a rare twist in an otherwise terrifying canon.

Modern Echoes and Enduring Legends

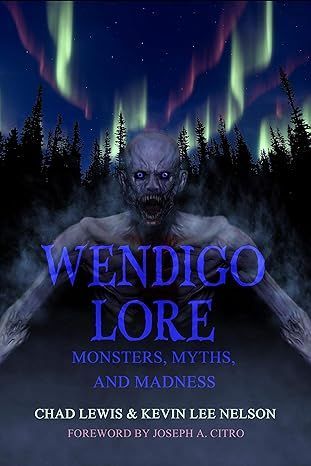

According to paranormal researcher Chad Lewis, the Wendigo is “perhaps the oldest folklore legend of a monster in North America—and ironically, one of the least known today.” In researching his book Wendigo Lore, Lewis traveled across Canada and the northern U.S., speaking to elders, visiting alleged Wendigo sites, and collecting chilling accounts from both oral tradition and colonial records.

One woman in northern Minnesota recalled her father warning neighborhood kids: “If you ever hear a kettle banging in the woods, run. The Wendigo is coming.” For her, even decades later, the fear was real.

You can listen to an interview I conducted with Chad Lewis discussing the Wendigo here or watch his 2020 presentation from the Milwaukee Paracon Online below.

Thanks to pop culture, the Wendigo now appears in:

- Movies (Ravenous, Antlers, Pet Sematary)

- TV series (Supernatural, Hannibal)

- Comic books and video games (Until Dawn, Marvel Comics)

But these portrayals often strip away the cultural meaning. To Indian communities, the Wendigo is a deeply moral story about balance, community, and spiritual health—not just a monster to be hunted.

Conclusion: Is the Wendigo Real?

Whether seen as a metaphor, a spirit, or a psychological phenomenon, the Wendigo legend endures because it speaks to something primal: our fear of what hunger and isolation can do to the human soul.

And if you ever find yourself walking through the snowy woods of Madeline Island or Bar Harbor, and you hear a kettle clanging in the trees—don’t investigate.

Run.

The Wendigo might be coming.